Kidney dialysis

Renal haemodialysis has come a long way since the 1940s, when Dutch physician Wilhelm Kolff built the first successful device using, among other items, sausage casings and parts of a washing machine. The following decades saw rapid developments in safety, effectiveness and technical sophistication. Nowadays, at any one time in the UK, more than 25,000 people are undergoing haemodialysis on account of kidney failure; some set to continue indefinitely on this treatment, others while they await a kidney transplant.

For over a decade, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has been recommending that more patients should undergo haemodialysis at home, but still only around 3% do so

Most patients receive their thrice-weekly, four-hour treatment in hospitals or other specialist centres – and in this lies one of the key remaining non-technical issues in contemporary haemodialysis. For over a decade, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has been recommending that more patients should undergo haemodialysis at home, but still only around 3% do so.

Some of the reasons for this shortfall are beyond the scope of engineers to tackle – but not all. Haemodialysis machines that are smaller and easier to operate in the home should make a move out of the clinic more feasible and more appealing. This is the intention behind several attempts to develop a new generation of home haemodialysis machines. In America, a machine called called System One, produced by NxStage, has recently come to market. Meanwhile, in Europe, French company Physidia has a machine called the S3 which is already in use. This has recently been joined by UK-based Quanta Fluid Solutions’ newer SC+. Developed over the past eight years, the SC+ became CE marked in January 2015, allowing use in the EU.

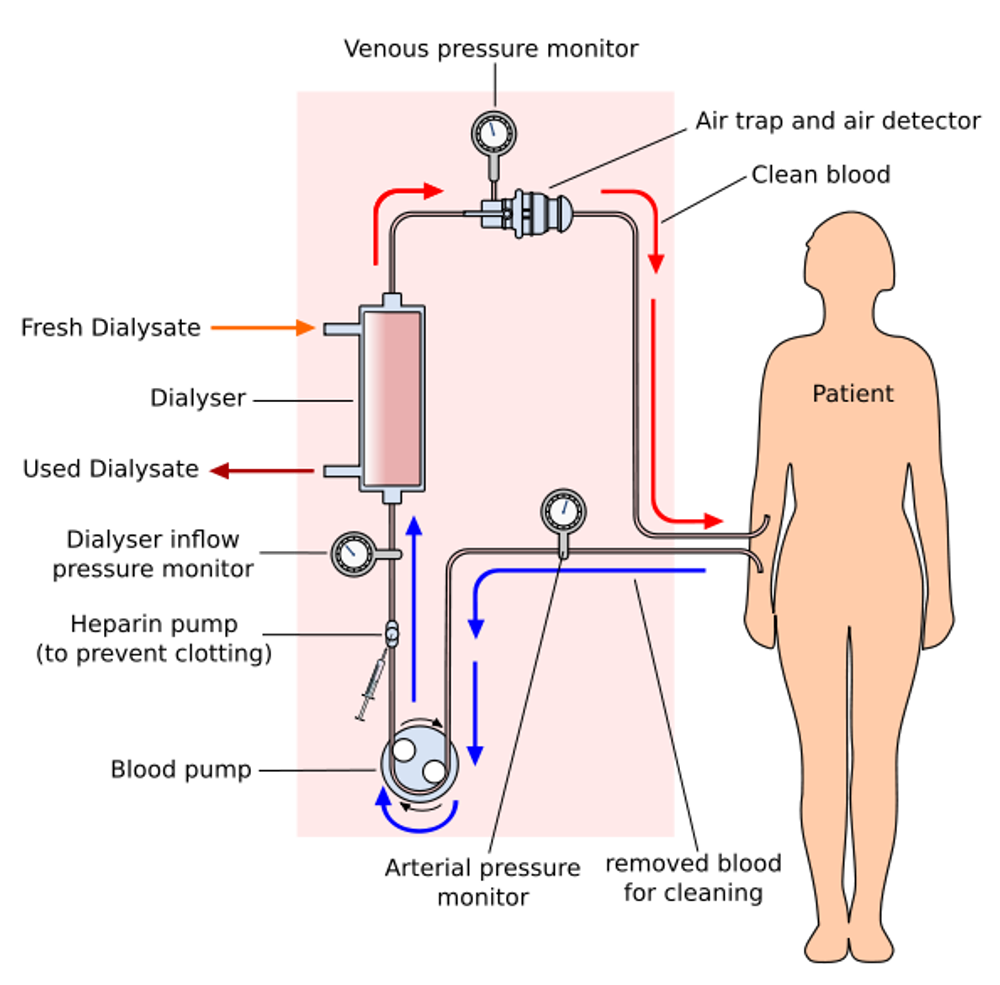

There are two main types of dialysis, haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis,which both remove wastes and excess water from the body in different ways. This schematic shows how haemodialysis removes wastes and water by circulating blood outside the body through an external filter, called a dialyser, that contains a semipermeable membrane

One's enough

Although we have two kidneys, we can get along very well with just one. This substantial over-provision means that kidney disease may already be far advanced before it is detected, often through a routine blood or urine test. With further loss of function, potential symptoms include poor appetite and loss of weight, blood in the urine, swollen ankles and feet, high blood pressure and muscle cramps. For end-stage renal failure, the final outcome of the disease process, there are two remedies: a kidney transplant, the ideal treatment; or dialysis. The latter may be used as a stopgap until a suitable donor kidney becomes available, or as a permanent solution.

The principle underlying renal haemodialysis (using an extracorporeal circuit, see diagram) is straightforward. Blood pumped from the patient flows over a semipermeable membrane. On the other side of the membrane, and flowing in the opposite direction, is a specially prepared fluid called a dialysate. Because any dissolved substance will diffuse from a region of higher to one of lower concentration, waste products in the blood - urea and phosphate in particular - will move across the membrane and into the dialysate, which is free of these materials.

Sodium and other substances required by the body can be retained by ensuring that the dialysate contains them at a concentration equal to that required in the blood. Cells and protein molecules remain in the blood, being too large to penetrate the membrane. Besides, extracting impurities from the blood, haemodialysis also has to remove excess water from the patient's body. This is achieved by ultrafiltration, which also takes place across the semi-permeable membrane. If the pressure of the dialysate is held at slightly less than that of the blood, water will migrate from the latter to the former. The amount to be removed- typically two kilos, but sometimes as much as four - is determined prior to treatment simply by weighing the patient. Finally, the purified blood is returned to the patient.

Every year, 25,000 people in the UK with kidney disease receive haemodialysis. Only a small proportion of these patients conduct their treatment at home; usually they visit hospital three times a week for three to four hours at a time © Anna Frodesiak, Wikimedia Commons

Pioneering achievements

The engineering challenges facing the pioneers who set out to mimic the role of the kidney were considerable. They needed peristaltic pumps that would not unduly damage the delicate red and white blood cells. They needed to monitor the blood’s temperature and pressure, and they required detectors to check that potentially lethal bubbles had not formed within the blood being returned to the patient. Machines had to be fitted with warning devices and backup systems to cope with any failure of the equipment.

Haemodialysis also required a considerable volume of pure water, up to 120 litres, to which were added the dialysate chemicals, principally sodium bicarbonate and acid. To avoid infections, the pipework through which the blood and the dialysate flowed needed a thorough cleaning and disinfection after every use. The first generations of the machines invented to do all this were bulky, cumbersome and required trained staff to operate them. But, step-by-step, engineering overcame these and other hurdles.

Although these early haemodialysis machines were intended for use in hospitals, the 1960s saw them beginning to be moved out into patients’ own homes. This further development threw up a new set of challenges, because they now had to be handled by patients themselves. Every session required the reassembly of reusable equipment.

The size of the machines, the complexity of their operation, the need for home alterations, the rigours of careful disinfection and much else militated against the switch. But pioneers and supporters persevered, and the number of patients on home haemodialysis, although never great, increased throughout the 1970s. It reached a peak in the early 1980s. Then, with the introduction of the immunosuppressant drug cyclosporine leading to an improvement in survival following kidney transplantation, the number of patients needing haemodialysis fell. At the same time, industrialised, commercial haemodialysis services and economies of scale at dialysis clinics led to the proportion of patients on home haemodialysis declining to its current low level.

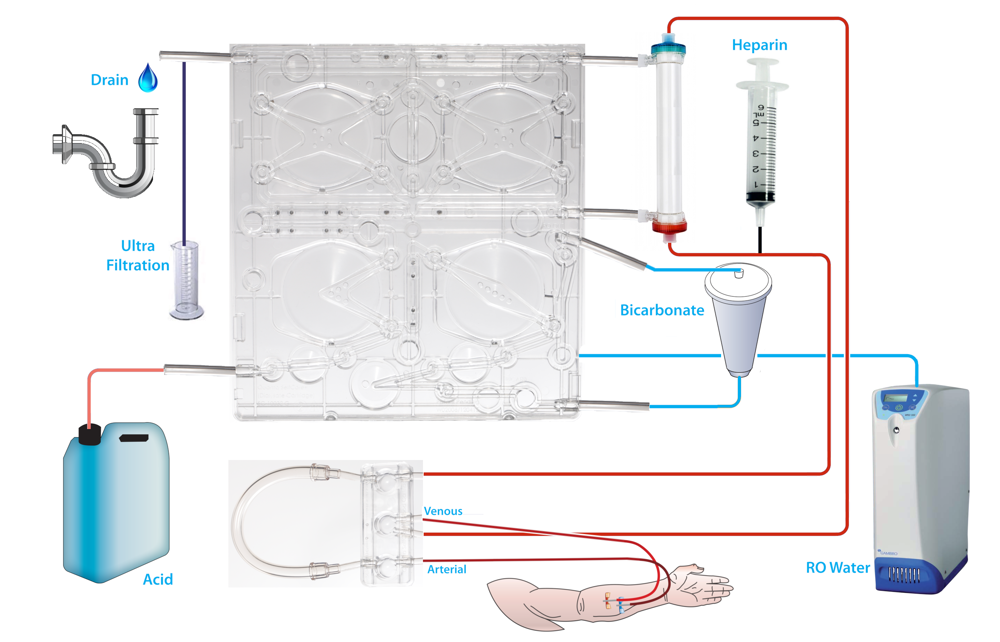

A SC+ haemodialysis machine schematic showing blood leaving the patient and the pathway it takes before returning. Water is produced by the reverse osmosis, mixed within the cartridge with acid and bicarbonate, before passing through the dialyser and draining along with the waste products from the patient © Quanta

A new machine

The UK-produced SC+ portable haemodialysis machine will help to drive the trend back to performing haemodialysis at home. It aims to relegate haemodialysis to a less demanding place in patients’ lives. It uses generic industry standard components, and key among these is a disposable cartridge comprising some 90% of the hydraulic pipework required in haemodialysis – see From juice to blood.

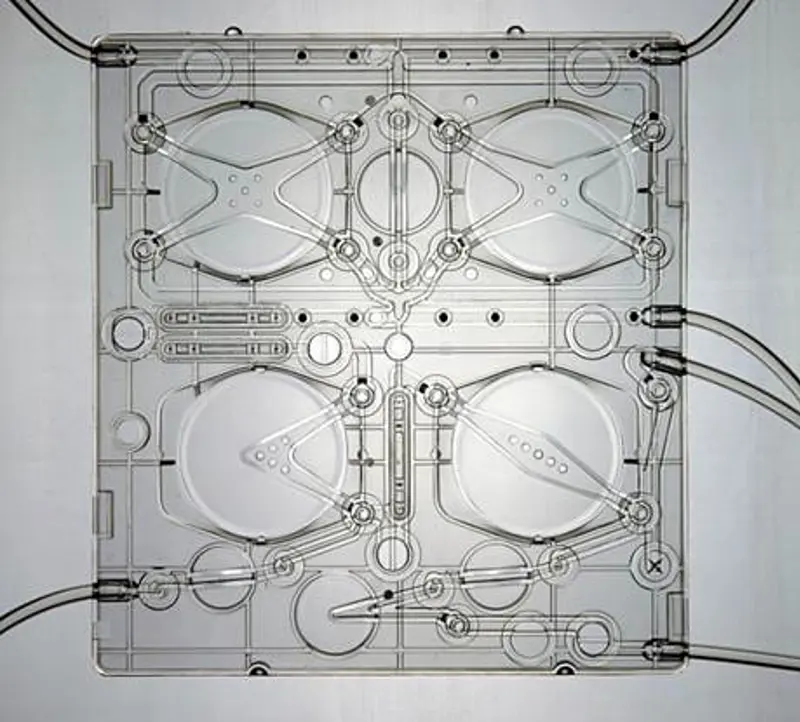

Its cartridge consists of a rigid rectangular polycarbonate injection moulding to which a PVC film is thermally bonded on either side. The form of the moulding, together with the film bonded to it, creates a number of fluid pathways for taking dialysate from the machine to the dialyser and back again before passing it out of the machine and onwards to the drain.

Once the cartridge has been inserted, the movement of the fluid through it is driven by the application of the pneumatic pressure to various areas of the PVC film that forms the mating face between the cartridge and the rest of the machine. Fluid is pushed and pulled through the cartridge by a programmable sequence of positive and negative pressures to four sets of pumps and valves lying behind the PVC film.

One pump takes water from the mains and delivers it to the haemodialysis machine via a reverse osmosis device; this guarantees the required biological and chemical purity. Some of this purified water is delivered to another small cartridge of bicarbonate powder.

The resulting bicarbonate solution, diluted by the main flow of water into the machine, moves onto a second membrane pump. This is responsible for introducing acid from a further resevoir, and delivering the now complete dialysate to two more pumps that drive it through the actual dialysing unit. The removal of excess water from the blood is achieved, as with all haemodialysis machines, by pressure-induced ultrafiltration.

The semi-permeable membrane within the cylindrical dialyser takes the form of a bundle of some 10,000 polysulphone tubes through which the blood is pumped. At roughly 25cm in length, the unit offers a dialysing surface area of approximately 1.8 m2. The dialysate is driven around the outside of the tubes by two membrane pumps, one pushing the fluid in, the other drawing it out. To overcome disparities in performance between the two pumps, they periodically switch rolls, thereby ensuring that any difference is cancelled out.

Although SC+ is as small as a microwave oven, it still has to be as safe as machines used in hospitals, with systems in place to double check that no faults have arisen

The cartridge, with its four pumps and their associated pipes and tubes, and the dialyser are only used once, then discarded. This eliminates the need for most of the cleaning and disinfection that makes conventional haemodialysis so laborious. Moreover, the small amount of cleaning still required is performed automatically when, as little as once a week, the machine goes into self-cleaning mode and flushes out hot water through the remaining short length of non-disposable piping.

Although SC+ is as small as a microwave oven, it still has to be as safe as machines used in hospitals, with systems in place to double check that no faults have arisen. Like its larger predecessors, the SC+ includes all the necessary devices for detecting bubbles, and for monitoring temperature, pressure and other indicators. For some of these needs, existing devices could be utilised; others had to be designed from scratch to suit the new machine. Apart from attaching themselves to the machine, the patient's only tasks are to top up the bicarbonate and acid supplies, key in the weight of water to be removed, and the change of the cartridge after every session.

From juice to blood

🧃 How the origins of SC+ relate to drink dispensing machines

The origins of SC+ were borne out of previous work on an unrelated project: improving the safety and efficiency of drink dispensing machines. The history of the project goes back to the middle of the last decade, when the firm now responsible for developing the haemodialysis machine was part of the engineering company IMI.

One section of IMI was developing equipment for dispensing drinks, including fruit juices. These are susceptible to contamination by various microorganisms, particularly during the cleaning of valves and nozzles when, for example, the machine is switched from dispensing one type of juice to another. A system was designed which enabled juice concentrate to be delivered in disposable bags already fitted with their own mechanism (also disposable) for diluting with water and dispensing. Refilling the machine, or changing the flavour being dispensed, became a procedure that required no cleaning. After consultation, it was felt that the principle of using a disposable unit would be equally applicable to haemodialysis machines.

In 2008, after 18 months of development, a spin-out company to work on this was set up. Quanta Fluid Solutions bought the relevant patents from IMI, which agreed to invest in the new company for a year while venture capital was sought to take the idea forward. The two original patents have now expanded into a family of 22 and form the foundation of Quanta’s future.

New medical devices have to pass a wide range of tests and certification procedures to ensure that both hardware and software meet the relevant safety and quality standards as authorised by the appropriate notified body. SC+ has recently received CE marking under the EU Medical Devices Directive which allows it free movement of products within the 27 member states of the EU and European Free Trade Association countries. Acquiring a CE mark was made significantly easier by the fact that all the inputs and outputs to the cartridge and the flow rates remain identical to existing machines used in clinics.

The SC+ cartridge showing chambers for mixing the constituents of the dialysate and controlling flow to and from the dialyser © Quanta

Expert inputs

The early progress of the project was helped by Devices for Dignity (D4D), a body based at the University of Sheffield and funded by the National Institute for Health Research to encourage the development of new products, processes and services for people with chronic health conditions. Besides canvassing the views of patients, D4D was also able to offer advice on the clinical need for the system, and what sort of device might be commercially viable. With their help, the project was also awarded an NHS i4i (Invention for Innovation) grant to support the work.

The biggest obstacle had been the size and complexity of the equipment itself. Now this engineering hurdle has been overcome

The Quanta SC+ is a portable single-pass haemodialysis system that uses a disposable cartridge to generate the dialysate for every treatment. As the machine itself is never in contact with blood or the treatment fluids (the pre- or post-dialysis dialysate), it does not need disinfection or sterilization.© Quanta

Now it will be seen if the machine is adopted by healthcare staff and patients. For some patients, the issue is one of confidence about taking responsibility for their own treatment. Others may live by themselves or in circumstances under which home haemodialysis is impracticable. Arguably, the biggest obstacle had been the size and complexity of the equipment itself. Now this engineering hurdle has been overcome.

Home haemodialysis continues to offer many benefits. Most obviously, patients have no need to travel three times a week to a hospital or clinic. They can dialyse on the days and at the times most convenient to them – which means they can do so four or five times a week instead of the more usual three when using a hospital machine. Frequent haemodialysis more closely resembles the continuous blood cleaning provided by the kidneys themselves. It also reduces the required time per session from the usual four hours in hospital down to two or three and patients can even dialyse overnight.

As with any medical treatment, home haemodialysis is not entirely risk free. Besides those facing all haemodialysis patients, some events – the accidental introduction of air into the bloodstream or the failure of one of the tubes carrying blood in and out of the body – are more of a threat at home than in a clinic with experienced staff on hand. But the patients and their helpers will be trained in what to do for such emergencies.

The end product is a machine flexible enough to be used in hospital as well as at home. A patient developing a complication that requires haemodialysis to be performed under medical supervision could still carry out the treatment themselves, but with a nurse around to keep an eye on things.

Early indications show that there is an enthusiasm amount both patients and clinicians to see much more home haemodialysis, and this approach to kidney failure is likely to become more prevalent. There is a gathering momentum for the idea that patients should be dialysing to live rather than, as it still the case for many, living to dialyse.

👀 See how the dialysis machine works

***

The author would like to thank Geoff Watts, science and medical writerand broadcaster for his help in writing this article

This article has been adapted from "Kidney dialysis", which originally appeared in the print edition of Ingenia 62 (March 2015).

Contributors

Professor Clive Buckberry FREng FInstP is Chief Technology Officer at Quanta Dialysis Technologies. He was part of the founding team that initially developed the concept of Quanta’s SC+ system and obtained initial venture funding. Clive Buckberry had previously worked for the BMW group with responsibility for the vehicle physics department. In 2001, he became an honorary professor within the Department of Engineering and Physics at Heriot-Watt University

Get a free monthly dose of engineering innovation in your inbox

SubscribeRelated content

Health & medical

A gamechanger in retinal scanning

2006 MacRobert Award winner Optos rapidly became a leading medical technology company and its scanners have taken millions of retinal images worldwide. There is even a display at the Science Museum featuring the Optos development. Alastair Atkinson, of the award-winning team, describes the personal tragedy that was the trigger for the creation of Optos.

Engineering polymath wins major award

The 2015 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering has been awarded to the ground-breaking chemical engineer Dr Robert Langer FREng for his revolutionary advances and leadership in engineering at the interface between chemistry and medicine.

Blast mitigation and injury treatment

The Royal British Legion Centre for Blast Injury Studies is a world-renowned research facility based at Imperial College London. Its director, Professor Anthony Bull FREng, explains how a multidisciplinary team is helping protect, treat and rehabilitate people who are exposed to explosive forces.

Targeting cancers with magnetism

Cambridge-based Endomag has helped treat more than 6,000 breast cancer patients across 20 countries. The MacRobert finalist uses magnetic fields to power diagnostic and therapeutic devices. Find about the challenges that surround the development and acceptance of medical innovations.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95