Wimbledon's technology is on point

Did you know?

- In 2024 the Wimbledon Championships were transmitted live to over 200 territories worldwide and watched by a TV audience of 133 million

- The Championships have a growing digital reach, with a 70% increase in video views on wimbledon.com and mobile apps in 2024. The total audience in 2024 was 670 million across TV, digital and social media

- Innovative technologies and data are transforming the Championships into one of the most technically advanced events on the international sports calendar

At the end of June, more than 250 of the world’s best tennis players will arrive in southwest London. Over two weeks, they’ll play 764 games, hitting 55,000 balls across 36 courts. More than half a million spectators will cheer them on, as they munch through more than 38 tonnes of strawberries.

While the players bring their A-game, dozens of people will work behind the scenes to bring the game to the fans. This backroom team will be maintaining hundreds of Hawk-Eye cameras, thousands of network outlets, and more than 140 kilometres of fibre-optic cables.

Overseeing all this is Bill Jinks, Wimbledon’s Technology Director. Jinks has worked at Wimbledon, or to give it its proper name, the All England Lawn Tennis Club (AELTC), for more than 20 years, first as an engineer at IBM, before joining the AELTC in 2018. Over that time, the club has seen continuous technological transformation, including the introduction of paperless ticketing and Hawk-Eye.

This year, the technology underpinning the iconic championships will evolve yet again, and in ways that may change the look and feel of the game. Hawk-Eye’s remit is expanding, while Wimbledon’s technology partner, IBM, is providing reams of data and analysis by harnessing generative AI – all with the aim of improving the experience for tennis fans, casual and nerdy alike.

For the first time ever, in 2025 Wimbledon will join the majority of the ATP tournaments and rely entirely on electronic line calling for all matches, replacing human line judges to rule on whether a ball is in or out of the court.

Keeping the club humming

"We are a year-round visitor attraction,” Jinks says, referring to the club’s museum and tours. “The grounds are open all year round for the members – we’re a members’ club, so a lot of the technology is still on.”

In the 50 weeks of the year there isn’t a world-famous tennis championship, Jinks and his nearly 40-strong team keep that technology running, including security, CCTV, access control, and booking and payment systems.

“They’re the mundane things, but they’re the important things,” he says. “There’s a full IT operation that’s running all year round. When we’re not doing that, we’re planning for the next championships.”

In early spring, the team starts its 100-day countdown to the championships, where plans for the tournament are tested and put into action. It will also install extra security cameras and Wi-Fi access points, build media areas, and lay yet more cabling – an additional 35 kilometres of it.

Eyes like a hawk

At the 2025 tournament, one of the most noticeable changes will be seen at the courts’ edges. For the first time ever, Wimbledon will join the majority of the ATP tournaments and rely entirely on electronic line calling for all matches, replacing human line judges to rule on whether a ball is in or out of the court.

Hawk-Eye, which has provided the club with ball-tracking technology since 2007, will also take care of the electronic line calling. Its ball-tracking system relies on a 2D vision system, which finds the ball’s centre, and a series of about 12 cameras positioned around the court that track the ball’s trajectory in 3D space over time, at a rate of 340 frames a second. It’s this trajectory data that determines exactly where on the court the ball has bounced, and whether it’s in or out.

When Hawk-Eye’s technology was first introduced, its slow-motion animated replay was solely to accompany the TV broadcast. Then came its formal use supporting umpires in player challenges, accompanied by enthused clapping from the crowd. In 2015, Luke Aggas, then Hawk-Eye’s director of tennis, told Sports Illustrated that in the early days of the technology, chair umpires and line judges were “nervous they were going to be shown up”. However, he added, players are typically only right 30% of the time, so most of the time, the umpire or judge could be confident they had made the right call.

Now, the officiating technology will take care of the ‘out’ and ‘fault’ calls that were always the territory of human line judges, though some will remain in place as backups. “Each court has a Review Official, a qualified tennis umpire, who monitors the tracking and camera feeds and is able to advise the chair umpire if something unexpected occurs,” Jinks explains. For ‘close calls’, the tracking system will send data to a visualisation system that generates the images on the scoreboards. These will take only a few seconds to produce and display.

A line-calling camera is installed on No.3 Court. In the background is a Tournament Information Display, which shows schedule, scores, results, and general tournament information for guests. It is the same LED technology as the scoreboards © AELTC/Chloe Knott

AELTC Chief Executive Sally Bolton said that the club had decided that the system was “sufficiently robust” enough, adding that it takes its responsibility for balancing tradition and innovation “very seriously”.

Although some players have complained about electronic line calling, the technology is more accurate than human line judges, and as one umpire put it, doesn’t feel the pressure “at five-all in the final set”. Sadly for anyone who loves the drama of a player challenge, these tense moments will be no more.

While ball tracking has changed the game when it comes to fair play, tracking the players themselves could unlock insights that improve their performance.

Hawk-Eye’s SkeleTRACK, debuted at September 2024’s Laver Cup, is a player tracking system that promises “greater accuracy” and “deeper biomechanical insights” into athletes’ performance. It uses an array of cameras that track 29 points on a player’s body, including shoulders, hips, ankles, and wrists. Image processing and player recognition translates that into those real-time player movement insights.

The insights from player tracking data captured by systems including SkeleTRACK help players better understand their biomechanics, or how they move, so that they can improve their game. “The data is made available to players’ coaching or performance teams,” says Jinks. These teams are using insights from the technology to help players adjust their technique, improve their efficiency, and reduce their risk of injury.

The insights from player tracking data captured by systems including Hawk-Eye's SkeleTRACK help players better understand their biomechanics, or how they move, so that they can improve their game.

Tennis isn’t the only sport benefiting from player tracking data. Varuna De Silva, a reader in machine intelligence and digital technologies at Loughborough University, used years of player tracking data from the Premier League to help Chelsea Football Club work out how elite players make decisions while under high-pressure situations. “The decisions could be who to pass to, when to pass, and what to do with the ball,” De Silva explains. “These decision-making skills are what makes an excellent player an elite player.”

The data gave them an average, or a benchmark, with which they could compare players’ performance. It also could be used in coaching to develop drills that would improve certain techniques, and prepare them for certain plays, so they get better at handling that psychological, or what is more accurately described as situational, pressure during play.

Bringing fans closer

Every year, Wimbledon’s technology partner, IBM, captures 2.7 million data points from the Championships. It’s not just the scores. For every single point, there’s data on types of shot (forehand? volley? drive?), serve direction, whether there was an error, how it was won, and more.

Over the years, IBM has been finding new ways to crunch and present that data in ways fans will enjoy. AI has opened up many more possibilities to please both the casual tennis viewer and the nerdiest fans.

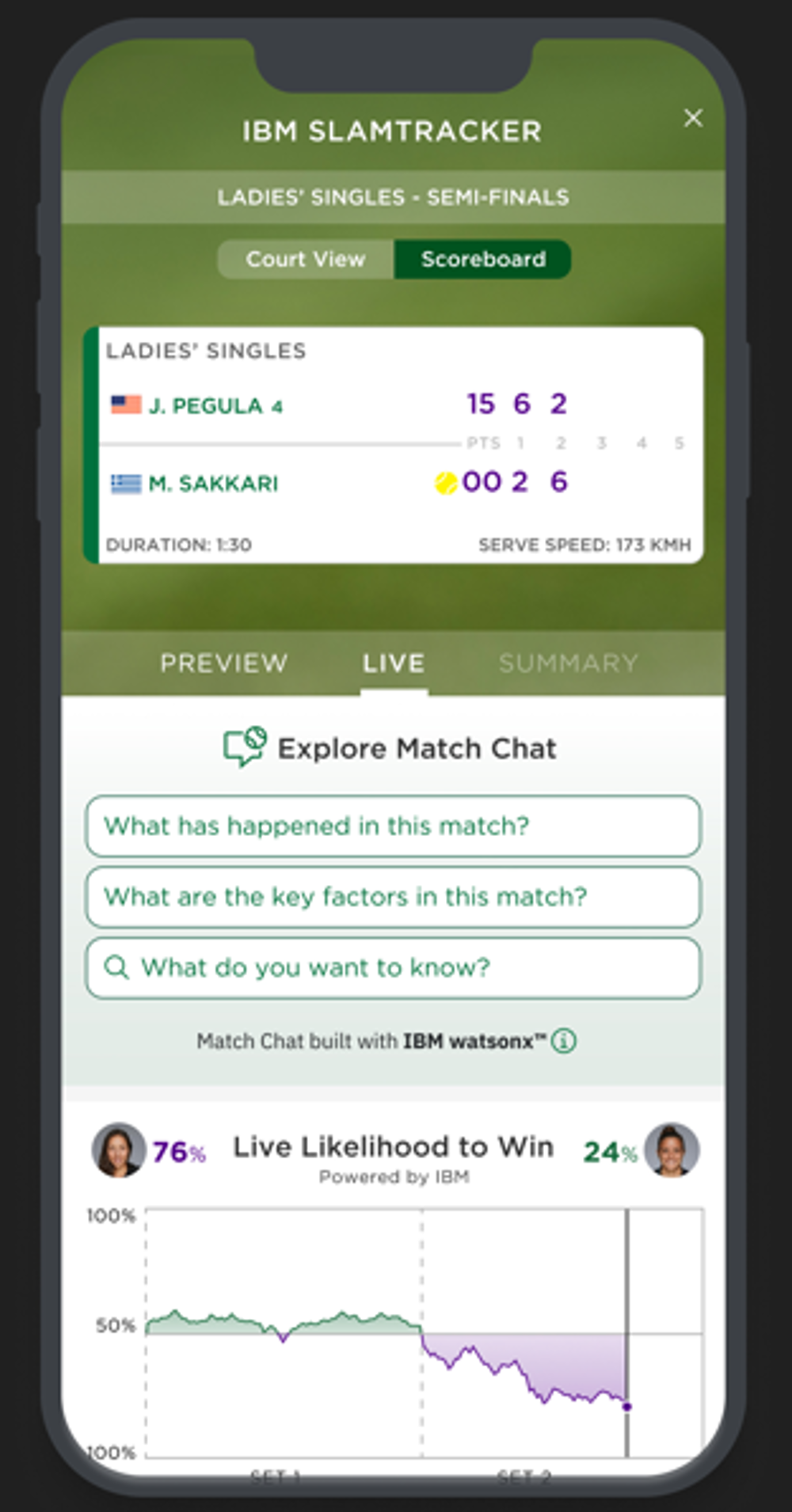

Slamtracker has been serving fans scores and statistics for more than 20 years. This year, IBM and Wimbledon will introduce an AI assistant to Slamtracker called Match Chat, which can answer fans’ questions, such as “who has converted more break points in the match?”, or “who is performing better?” during play, and in Wimbledon’s distinctive language. IBM has also updated its Likelihood to Win tool, which gives fans a projected win percentage that changes throughout the game. This percentage is generated from AI analysis of player statistics, expert opinion and match momentum. Fans can access these tools through the Wimbledon app.

IBM has also updated its Likelihood to Win tool, which gives fans a projected win percentage that changes throughout the game. This percentage is generated from AI analysis of player statistics, expert opinion and match momentum.

IBM's SlamTracker app for the championships now includes a chart showing live 'Likelihood to Win', which projects which player is likely to triumph based on moment-to-moment data and AI © IBM

Evidently, the Wimbledon championship generates an abundance of data – a real treat for tennis enthusiasts, but perhaps alienating to the casual viewer if presented the wrong way. How does the team avoid blinding the audience with science?

“One of our challenges is trying to get the right data for the right experience, for the right users,” Jinks says. “Wimbledon isn’t just a sports tennis event; it’s a cultural institution in the UK.”

He knows that for a lot of viewers, Wimbledon is the extent of their tennis viewing. “They may not be regular tennis fans, they may not even be sports fans, but they’re always going to tune into Wimbledon. And you have to be mindful that they’re not going to understand a lot of the tennis jargon,” he says.

For instance, a casual viewer may not have been able to identify Carlos Alcaraz’s chip return or high looping forehand against Novak Djokovic in last year’s men’s singles final, but a tennis buff reading or listening to the match commentary would be able to picture those shots immediately.

“It’s finding a balance for the mass audience, but giving them the ability to drill down, if you’re a real tennis fan and you want to see all the data,” Jinks says. “We provide a comparison of all the traditional statistics, including serve, return and point outcome statistics. For those that want to dig deeper, we compute and compare a shot quality index for serve, return, forehands, and backhands.”

How is Wimbledon dealing with generative AI’s tendency to, to put it bluntly, sometimes make things up? AI-generated responses aren’t always accurate, given they build sentences by making their best guess at what words should come next. As they’re trained on vast amounts of data, they do often make the right guess, although they can sometimes generate responses that are nonsensical, or plain wrong, in what we now call ‘hallucinations’. To avoid this, Wimbledon has a review process in place – a hallucinated game score wouldn’t exactly fly under the radar.

In recent years, Wimbledon and IBM have also used AI to generate video highlights and basic commentary. Where earlier AI models would have relied upon ‘factual’ game data, such as when an ace is hit or a break point comes, to generate video highlights, machine learning models are now a lot more sophisticated.

Using data from the Hawk-Eye system, they can identify the most exciting parts of a match and what’s worthy of a highlight, by watching players’ movements and gestures – whether players are running wide or fist-bumping a doubles partner – and listening out for a roar from the crowd.

Using data from the Hawk-Eye system, IBM's AI models can identify the most exciting parts of a match and what’s worthy of a highlight, by watching players’ movements and gestures – whether players are running wide or fist-bumping a doubles partner – and listening out for a roar from the crowd.

“The model can pick up on those nuances and become better at understanding what a good point looks like,” says Jinks, and with “ever-increasing accuracy”.

The technology also generates spoken commentary – with optional subtitles – that fans can lay over their video highlights. It’s done by watsonx, IBM’s AI platform. The large language model that powers the commentary was trained on source material from nearly 130 million documents.

Game changers

The availability of match data is transforming virtually every aspect of sport – from officiating and coaching to talent discovery and equipment design. Advances in machine learning will continue to change the game.

“The latest breakthroughs in sensor technology, computing power, computer vision, machine learning, and natural language processing are poised to revolutionise the field in ways that were unimaginable just a few years ago,” says John Bronskill, a postdoc in the University of Cambridge’s Machine Learning Group. “Professional sports organisations will increasingly depend on data scientists and information engineers to gain a competitive edge.”

De Silva is interested in how technologies such as Hawk-Eye and IBM’s machine learning platforms, now commonplace in elite sport, can be translated to grassroots level clubs. “We are talking about AI that can work off a mobile phone camera,” De Silva says. “It is what we would aspire the technology to do for the world.”

We’re already starting to see it happen. In 2024 the International Olympic Committee dispatched a team of talent scouts to Senegal in an effort to find the country’s future gold medallists. After recording about a thousand young people completing athletic drills, and measuring their performance with an AI-powered system by Intel, it identified 48 young athletes with “huge potential”, and one with “exceptional potential”, who have been offered places on training programmes to develop their talent, according to the BBC.

Ready to serve

As the world’s oldest tennis tournament, Wimbledon has to pull off a challenging balancing act of retaining beloved traditions while embracing innovation. Electronic line calling will make the game fairer – it’s simply more accurate than human line callers – although their absence will surely be felt by many Wimbledon fans this year.

Over the past 20 years, AI and social media have enabled Wimbledon to engage fans with the sport in new and different ways. “[They’ve] changed our approach to fan engagement, including both the content we create and the way we create it,” Jinks says. What might the next 20 years bring for the fan experience?

“We are always interested in new ways fans are going to consume the championships if they are not visiting the grounds,” he says. While the club has discussed the use of VR and AR for many years – it ran an AR pilot with IBM back in 2010 – interest in VR is limited by the level of adoption of the devices that can deliver it.

More broadly, sports organisations are looking for ways to find new fans as live TV audiences dwindle. For example, the Australian Open this year broadcast an almost-live, free-to-watch version of its matches on YouTube. The only difference between these broadcasts and what you could see on TV? The stream was an animated version of the match.

These animations were generated using real-life tracking data from the court, and aired two minutes after the live action. Tennis Australia told BBC Sport that its goal was to “captivate a new generation of tennis fans”, and “mak[e] the sport more accessible and engaging, especially for kids and families”.

In terms of content, the animations don’t miss any of the actual game content, matching them shot for shot, even if they do sometimes glitch out. Could this be a glimpse into the future of sport spectatorship?

With the first ball of this year’s Wimbledon Championships due to be served on 30 June, what should viewers expect this year? “Look out for how we’re bringing the data to life in broadcast,” Jinks says.

Over on the Wimbledon website, fans will also be able to see visualisations of points played. “You’ll see the ball track and the player tracks on screen, if you want to see how the point was played,” he adds.

With the club open year round, does Jinks’ team ever take a break? “In July, once the tournament’s over, we pack it all back in a box, and then go and have a holiday … and then we start planning again.”

Contributors

John Bronskill is a postdoctoral research assistant in the machine learning group at the University of Cambridge. He holds a master’s degree in electrical engineering and a PhD in information engineering. Previously, he co-founded ImageWare R&D, which was acquired by Microsoft, where he worked for more than 20 years in various technical leadership roles.

Bill Jinks is Technology Director at Wimbledon where he leads the technology team that delivers the Championships. Before joining Wimbledon, Jinks was a distinguished engineer at IBM, where he oversaw complex integration projects and transformation programmes.

Dr Varuna De Silva is a reader in machine intelligence at Loughborough University. He leads a team of researchers in fundamental AI algorithm development driven by real-world requirements, such as team sports analysis and autonomous drone systems.

Get a free monthly dose of engineering innovation in your inbox

SubscribeRelated content

Sports & leisure

How technology enhances the Wimbledon tennis experience

The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club (AELTC) and IBM worked closely together since 1990 to harness innovative technology to transform The Championships into one of the most popular and technically advanced events on the international sports calendar.

Noise-cancelling headphones

Used by plane and train passengers wanting to listen to radio, music or film without hearing background noises, active noise-cancelling (ANC) headphones are able to prevent outside noise from leaking through to the inside of headphones.

How to create the perfect wave

From small waves lapping at your feet and swells suitable for surfing to storm waves for testing structures and even tsunamis, waves of any shape and any size can now be engineered. What are the techniques and conditions needed to model waves and what makes some more powerful than others?

The technology that helped Team GB's cyclists go for gold in Rio 2016

The success of Great Britain’s cycling team at the 2016 Rio Summer Olympic Games was celebrated, but what about the closely guarded technology that contributed to their success? The engineering approaches taken to shave as much time as possible off the clock are spoken about by Professor Tony Purnell.

Other content from Ingenia

Quick read

- Environment & sustainability

- Opinion

A young engineer’s perspective on the good, the bad and the ugly of COP27

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95

How do we pay for net zero technologies?

Quick read

- Transport

- Mechanical

- How I got here

Electrifying trains and STEMAZING outreach

- Civil & structural

- Environment & sustainability

- Issue 95